anger can be a force for good

I grew up in a household with lots of misdirected anger, mostly from my dad. He was generally an angry person. Frequently, that anger would be directed at me, usually in the form of abusive language. Sometimes it was yelling. Sometimes it was undue punishment. Sometimes anger came in a form it took me years to identify: absence (both emotional absence—distracting himself with TV, etc.—and physical absence—leaving the house and spending the whole day with himself).

Is anger just a blanket statement for “things this person does that I don’t like?” Of course not. In fact, anger—expressed correctly—can be the most powerful force for good (we’ll get to that in a second). But all too often, our experiences with anger are negative. Because it is volatile, and at times, uncontrollable. But again, it bears repeating: anger can be a powerful force for good when expressed correctly.

What is anger?

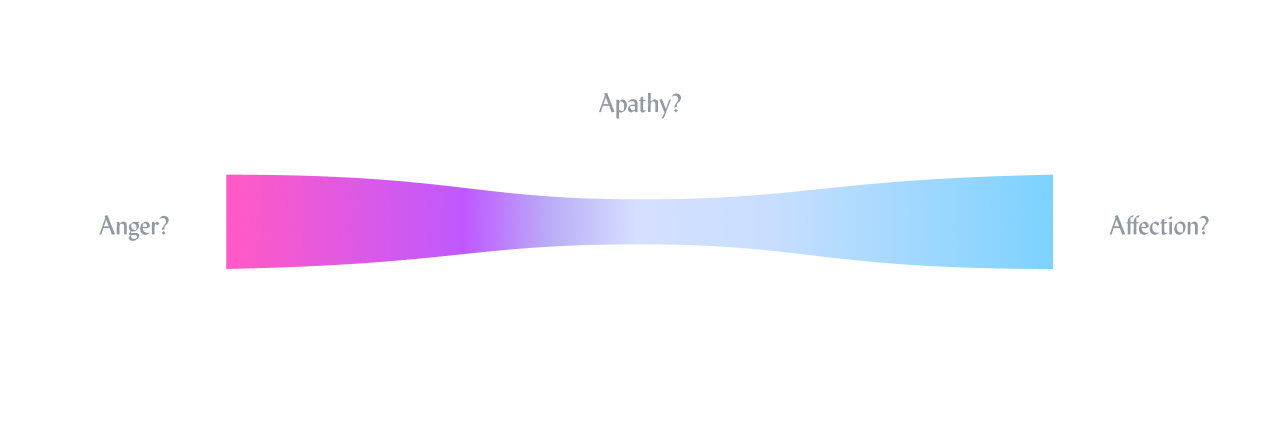

If you asked most people to define anger, you’d get a lot a lot of answers like “the opposite of love.” A typical misunderstanding of anger as it relates to emotions like apathy and affection probably looks something like this graph. On one end, you have “anger” (bad). On the other end, you have “affection” or “love” (good). And somewhere in the middle, you have neutral—not caring. When you try and map this common misconception to good/bad/neutral, you wind up with a spectrum like this:

If we’re honest, a lot of us incorrectly think of anger like this. We all know dramatic people that can be elated one moment, furious the next, and content the next. Or how quickly do our feelings toward a fictional character go from affection to anger when it’s revealed they were a traitor? In those rapid, sudden mood shifts, are we to believe there was somehow an apathetic phase in there we just rushed past? When affection can turn so quickly to hate, and back again, is there a split second of complete apathy in between?

Unlikely.

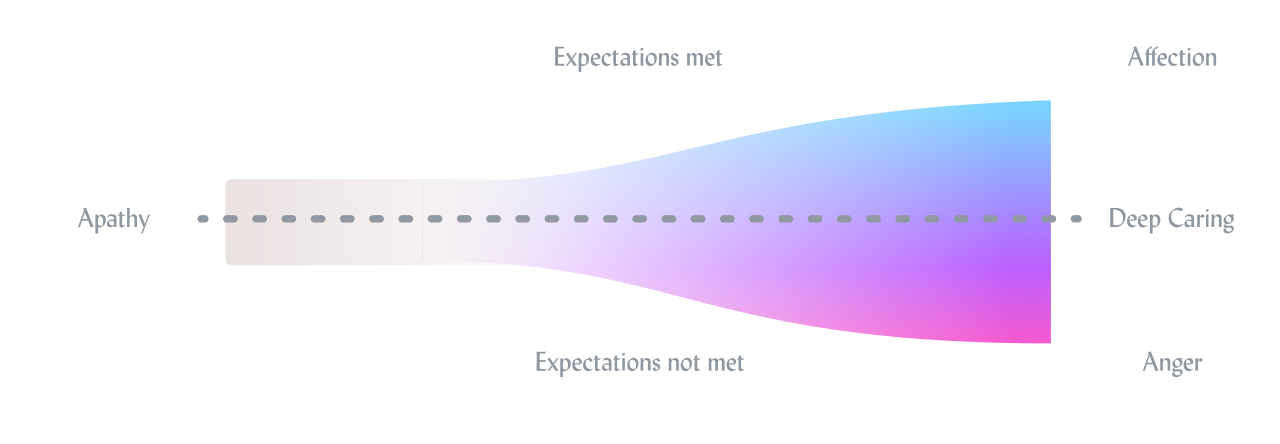

Apathy might be misplaced, then. What happens if we bring two other concepts into the mix: amount of caring, and expectations?

Affection and anger are both deeply-caring emotions. That’s why they can flip at the drop of a hat. On the extreme opposite end is apathy: simply not caring either way. What completes the picture for us are expectations: our wishes, desires, and opinions on how reality should be, and whether or not that is actually what’s transpiring.

We get angry at injustice. We get angry at people we love when they hurt themselves. We get angry for people we love when someone harms them. We get angry at ourselves when we fail. In all of those scenarios, anger is at the intersection of caring and unmet expectations. Something happened that we wished did not, and we cared deeply about it.

No one gets angry over something they don’t care about.

Wait — aren’t you confusing “anger” and “disappointment?”

Disappointment, like anger in this graph, indeed comes from failed expectations about something we care about. But I would postulate the difference between the two is acceptance. We’re disappointed by things we wish were different but accept them as they are. We’re angry about things we expected to happen differently, and we can’t accept the outcome.

A force for good, you say?

What took me a long time to realize—and it came from having conversations with my dad as an adult—was that he had a lot of failed expectations. For his life, for his marriage. His picture of what the world should be was very different than what it actually was. However, he did little to change it, other than find ways to numb his pain.

Revisiting the statement “anger can be a force for good when expressed correctly,” we can see that all the great social reforms of history came from a place of anger. Anger that the world isn’t as it should be. Anger over evil prospering. Anger over the downtrodden that should be lifted up. Great men and women that called for change in history cared deeply, and were not happy with the state of things.

They were angry.

However, that angry energy was often directed into fruitful things: protests, rallies, petitions, speaking engagements, etc. Social reform came from the pain of unmet expectations, but they did something about it, rather than beat their fists and lash out at anything and anyone possible.

Looking back, many of the people in my life—myself included—cared deeply for something and had expectations broken, but the response usually resulted in no change other than hurting everyone within range. The conditions were there for powerful change. In my dad’s case, I think it was largely self-directed anger at his own failed expectations for his life. But rather than use that as an energy to change himself, or help others not make the same mistakes he did, he chose to lash out and hurt those that didn’t deserve it.

Few people would describe me as “angry;” In person I’m generally deadpan, even-keel, and don’t raise my voice. But I get angry very frequently. I’m not intimidating. I don’t rage. I’m not seething on the inside. But several times throughout the week (my wife can attest to this), I get pretty angry about something about the world that isn’t right. While I’m nothing close to a social reformer, people would describe me as productive and driven. What I really seek is change within my household and my community, and that takes many forms.

Realizing when we’re upset about some part of reality—whether that’s the world around us, or something inside—the only response that benefits anybody is making steps to change it. It’s OK if you do this while angry. So long as you’re kind and dignifying (that’s the important part!) to everyone around you, anger can be the catalyst for immense good in this world.

Get angry. So you don’t have to be anymore.